Copying a work of art: Neglecting the realm of meaning

The following text will delve into the issue of art forgery. While this issue may initially seem tied to the art economy, with the sale of counterfeit works damaging art markets, galleries, and other art economy institutions, the harm extends beyond the economic and market realms. Copying a work gives rise to other challenges that we will attempt to explore in this brief article. It is evident that when we speak of a 'work of art,' we mean a work that has undergone an 'artistic process' and transformed into an art object. In fact, what we call a 'work' is a process of which the art object itself is one aspect (the physical aspect), while the other two aspects are the artistic impact and the artistic process. These two, like the work itself, play a significant role in creating and conveying meaning.

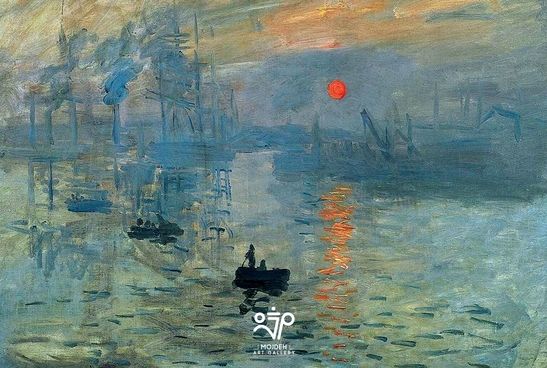

In any sign system, including painting, we encounter two communicative dimensions that are interrelated and produce verbal and nonverbal language. We refer to these two dimensions as the expressive plan (map of expression) and the contentual plan (map of content). These two, in fact, address the external and internal worlds of the text. In other words, a disconnect between the expressive plan and the contentual plan can plunge a (literary/artistic) text into a state of pure formalism (by focusing solely on the contentual plan) or can prevent the text from engaging in any formal interactions with contemporary texts, resulting in a meaning that is not coextensive with its form (by emphasizing form alone). To provide an example of these two plans and to delve into the fascinating world of artistic puzzles that harmonize form and content, we will consider an example from the medium of painting:

In a work of art, colors, lines, and composition constitute the external, formal aspect and are connected to the expressive plan. In other words, they fall within the realm of the work's form. The interconnections of these colors, the creation of a color palette, and the overall composition work together to convey the artist's intended meaning within the contentual plan. In essence, there are layers of meaning for the artist, and the viewer can, to a certain extent, reach the threshold of these layers (although they remain on the threshold of semantic understanding). This is the inherent nature of painting: it only provides a portion of the puzzle to the viewer or audience. It's important to remember that these two plans are not static. Meaning, or the contentual plan, is constantly evolving and shifting. For instance, the completion of a painting, being linked to the concept of time, can itself become the contentual plan until the meaning is fully realized. Therefore, in all verbal and nonverbal languages, we encounter these two linguistic levels. However, distinguishing between these expressive and linguistic levels is easier in literary discourse than in visual discourse, especially painting. Every painting offers both the painter and the viewer an opportunity to immerse themselves in a world of signs. We find ourselves within the painting, and through this occurrence, we approach the realm of meaning. It must be acknowledged that the paths to meaning are traversed through composition, color use, or the removal of color (in essence, one cannot reach the contentual plan without form). Thus, the painter, like us (the audience, the viewer), is on a journey of producing and understanding meaning. They are the ones who draw us closer to the realm of perceiving meaning. This realm is polysemic and multifaceted, resulting from both the rational and the sensible. It is rational in that thought is one of the vehicles of the work, and sensible because the creation of a work always involves a kind of multisensory combination for the painter and in viewing for the audience. Another key point regarding the work is that every artwork is a creation. In fact, the work is both created and recreated each time it is seen. This process is perhaps one of the most critical concepts for interpreting a work, as the viewer's and the painter's realms of meaning intertwine each time, creating a new and even innovative meaning.

Based on what we have discussed, in nonverbal languages, achieving a unique style requires persistence in both the expressive and contentual plans. In addition to the need to construct and refine the architecture of these two realms, we must also consider other factors involved in the formation and production of meaning: factors such as the identity of the subject and narrative elements like 'I', 'here', and 'now'. Reaching a unique style is a journey through various paths and elements (both meaningful and formal) that must be carefully examined and analyzed. As a result of these factors, the painter creates a new realm of meaning with each painting in their visual discourse. This is the difficulty of the artistic path that Nizami refers to:

Come and see me as a dig a well

Digging a well as if I am tearing my heart out

The constant exploration of meaning that an artist undertakes, Nizami has described as 'digging a well' and 'tearing out one's heart.' Even if an artist has developed a signature style, this personal signature carries a new, unique, and personal meaning each time a work is created. This meaning is a result of deep contemplation within a historical and psychological time. This second time, the participation and presence of the artist's subconscious in the realm of imagination, is crucial. In fact, this life within the realm of imagination, which is the foundation of the medium of painting in particular, arises from a time when imagination has reached a depth of contemplation. The world of imagination is not limited to images alone; the psychological time connects images and then fosters thought about them. This time is unique because it represents the artist's personal relationship with the outside world; it is a response to their inner call, and therefore, only they exist in such a realm. Given the above, copying another artist's work means using an expressive plan and therefore a complete or partial disconnect from the contentual plan, which in a painting are intertwined like warp and weft and cannot be separated. Disconnecting them means being absent from the essence and identity of the text both in its own time and in subsequent periods. The relationship between expression and content is necessary, not optional; one cannot exist without the other. In such a realm, as Derrida writes, signs do not merely refer to the signifier and the signified, but also involve a vast realm of the imperceptible. (Derrida, 1397) Under these conditions, the second narrator (the copyist) has not 'dug a well' themselves but has merely attempted to drag another's 'well-digging' into their own thoughtless abyss, a bottomless pit. It is worth noting that even the form they create lacks value systems, because as Fontanille states in his book 'Semiotics of Discourse,' 'form is the locus of value systems.' (Fontanille:1998, p.39) Therefore, the value system of such a form is valueless. Knowledge does not lie in division, and there is no value in division.

Therefore, when we talk about copying works of art, we are referring to the severance of this necessary connection, which is based on the perceptual position of the painter within the artistic discourse itself. In painting, the sensible and the rational appear simultaneously to the creator, and they proceed to create. However, what is known as copying is the result of a disconnect between the sensible and the rational, because the sensible perception is only revealed to the original creator, and it forms the overt and underlying world of the painting.

The process of creating a work of art, as we know, involves not only aesthetic aspects but also ethical ones. These ethical aspects are generally revealed to the viewer during perception, in such a way that the viewer feels like a partner in a part of the work. When we talk about the ethical aspect, we mean aspects that are present within the individual and involve the individual's will. Many of our painters have used these ethical aspects in their paintings to convey mystical, moral, and other meanings. Now, in a copied work, since it does not belong to the original creator, it lacks ethics from two perspectives: First, copying a work is unethical and places the subject in a purely material position, exempting them from any artistic judgment or understanding. Second, the copied work lacks the ethical aspects of the original work. The value system of a painting, which produces meaning for the viewer through the connection of sight and perception, suspends the viewer in an ethical dimension. This is because we move through meaningful paths that the original painter's body has not traversed, and therefore, even if a copy is completely identical, it means a perception outside the meaningful path of the original creation.

Let us not forget the 'other' who has paved many unexplored paths for artistic creation and opened up unseen horizons. This 'other' stands before us in their most original and authentic form. This authenticity stems from the worldview that the original creator had towards the world and the 'other'. Disregarding their rights and copying their works means disregarding the 'other' who is the foundation of our understanding in the world.

Sohrab Ahmadi

- Derrida, Jacques (3rd Edition, 2018). Writing and Difference. Translated by Abdolkarim Rashidian. Tehran: Nashr-e Ney.

- Fontanille, Jacques (1998). Semiotics of Discourse. Limoges: University Press of Limoges.

- For further discussion on ethics and the internal system of morality, please refer to Dr. Shairi's article:

Shairi, [Author's Name]. "Ethics, Pahlavani Ethics, and Society." Farhang-e Rooz.