The Driven Saints

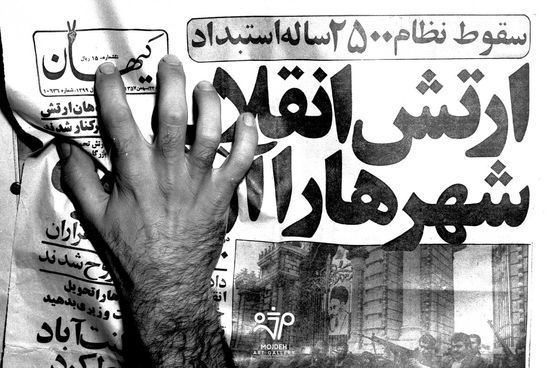

Mehdi Sahabi is a painter, sculptor, photographer, translator, writer, journalist and an irreplaceable genius who has made the entire material world around him a tool to express his feelings and ingenuity. Sahabi gives new essence to everything he sees; like the new life he gives to a piece of wood by turning it into a happy migratory bird that has been sitting joyfully on a wire of light in his mind for years, or a sparrow that has been soaked in his painting pool and now hangs with clothespins to a garden collage in his heart.

It seems like to him, every object has an independent identity and sometimes human character: in Sahabi’s mind the “car” is not just a piece of man-made technology, but a human being who in the process of industrial life has turned into a machine and borne the burden and responsibility of his time. A human being that has been abandoned as a junkyard car in a corner taking its final breaths far away from the hustle and bustle of life.

The “car” has been such an important and influential subject for Sahabi that he was never able to ignore it during his artistic career and focused on it in four different collections from the 80s to the 2000s. His first and most significant collection was “Junkyard Cars”, the second was “Junkyard Cars and Figures”, the third was “Puzzle Cars”, and the fourth collection, which is the subject of this article, was “Icons”. This collection is reminiscent of Byzantine art, a school of art with religious concepts, two-dimensional structure, flat, and always a promoter of the Roman Empire, and thus the Orthodox Church.

Unlike the “Junkyard Cars” collection, Sahabi’s “Icons” include eye-catching and classic old cars that are not scrap or broken down, but immersed in solid hues of red, blue, green, orange, purple and gold. At first glance some of these cars are depicted with plate numbers containing ambiguous letters such as ICO or IKO. But what is the secret behind these ambiguous letters? The neutral letters seem to stand for two words, “Icon” in English and “Ikonen”,the Latin spelling of this word. Perhaps with these letters in addition to naming the collection “Icons”, Sahabi is trying to leave clues for viewers asking them to look at his artwork from a different perspective.

The bright headlights of Sahabi’s iconic cars are reminiscent of the theory that “if the world looks beautiful, its beauty is due to the reflection of the image of the soul in it… Plotinus believed that since the soul is light, shadow and darkness should be avoided in artworks.” (Ghavami, 2012, p.32). It seems as if with the golden halo of light around their headlights Sahabi has blown a soul into his cars. With full knowledge of the structure of Byzantine art, using rich colors, and especially by placing golden halos around them he transforms his car headlights into the formal faces of Byzantine saints with their calm stiff bodies, standing full-faced, without any highlights or contrast. The colors in this collection are used similarly to the “Byzantine tradition [which] gave great importance to color and did not mix colors together… [and] used them purely” (Taheri, 2011, p.77). This collection is close to the “Novgorod” school of Russian iconography, where the color red was frequently used for icons and in the depths of the paintings. Colors have always contained specific and symbolic meaning in iconography, for instance the color white indicates divine light, purity, chastity and the infancy of Christ; dark and light blue indicate the sky, the eternal world, the connection between the earth and the sky, and are also the symbol of Mary; while the color green symbolizes hope and rebirth and in most icons the ground is painted green. Purple expresses impurity and human nature, and black is not a concept like death or evil. (Taheri, 2011, p.78).

Sahabi creates his icons like Russian Byzantine artists, who due to the abundance of a material like wood, and from their experiences of fear and relentless attacks, had learned to create small and portable artworks on small wooden panels painted with tempera. But unlike Byzantine artists, what Sahabi strongly believes in is the importance of the artist’s individuality. Because after all, these enlightened saints are the product of his imagination and Sahabi is their unquestionable creator. As a result, most of the artworks in this collection are signed, contrary to Byzantine custom in which artists because of their devotion and self-sacrifice “generally did not leave behind their names or signatures [except for a few cases]” (Iranpour, 2019). And unlike the Byzantine period where “the artist was subordinate to the artwork” (Spur, 2002, p.160) “because the artist had devoted his artwork to religion, and did not believe himself deserving of any individuality, technique, and reputation”(Iranpour, 2019), in this collection Sahabi’s personal view and techniques are highlighted.

Perhaps, it can be said these cars excuse me, icons! offered a glimmer of hope for Sahabi. As “Umberto Eco writes about the principles of aesthetic and medieval art: the period we speak of has been known as a period of darkness and contradictions throughout history; yet philosophers and the clergy at that time had an image of the universe in their minds that was full of light and optimism.”(Norouzitalab, 2017, p.5) It is as if with this collection Sahabi uses the form of old cars (not destroyed junkyard cars, but classic cars) to record in his visual memory superhumans with spiritual and extraterrestrial values; superhumans who like driven out saints appear in the form of cars by which Sahabi drives out into the medieval road of his time to achieve his dreamy utopia, unfettered and free.

Shakiba Parvaresh