A Journalist who Took Shelter in Painting

Mehdi Sahabi was an adroit translator who added many masterpieces to our literary treasures. Translating “In Search of Lost Time”, which many thought of as untranslatable, marked his name in our literature history.

Mehdi Sahabi is also a well-known figure in Iranian painting. He had much to say on this matter, which unfortunately remained unsaid. Perhaps his idea of “Junkyard Cars”, which began many discussions, will remain the subject of many more in the future.

Mehdi Sahabi’s visual artworks, especially his collection of “Birds”, which he loved dearly, reveal the power of his creativity, even though his short life did not allow him to make as much progress as he wished.

Mehdi Sahabi worked artistically, tirelessly, and humbly in different fields. He avoided pretension but became renowned. Yet there are not many who knew him as a journalist, and few realize that he could have been one of Iran’s international journalists. He had all the qualities for an international journalist but did not live in the right place and the right time. In my opinion, if he had lived in a different context, he would have been an international face in journalism.

In search of the way

Sahabi, who had a peaceful, harmonious, and affectionate childhood, entered adulthood with an artistic nature and a curious mind. He was more erudite than his friends and tried to polish his artistic nature and achieve more skills and abilities to express and transmit his artistic feelings and thoughts. He left Tehran School of Decorative Arts halfway through, and being relatively proficient in English he travelled to Italy. He left his film studies halfway through as well and he began to study painting at Rome Academy of Fine Arts. Leaving things “halfway” might be seen as a sign of boredom and indecision for people who are not familiar with Sahabi’s character, but Sahabi was too wise to waste “time”. He was an alert, curious man who would leave if he believed there was no longer a need to remain in one place! After spending two years in Italy, working and learning the language, he left for France. Three years of living in France and becoming fluent in French was enough for him to know it’s time to return to his homeland. So after five years of living in Europe, he returned to Iran in 1972, and the future revealed that he did not come back empty-handed.

Sahabi was interested in cinema, but very soon he learned that he had another calling. He began working as a French and Italian translator for Kayhan Newspaper’s international issue. The editor of the international issue at the time, Farahmand, was himself a prominent journalist, and said to Dr. Mesbahzadeh, the owner of the newspaper, “A number one talent has come to Kayhan.”

At that time two national newspapers, Kayhan and Ettela’at, were published in the afternoons. In comparison to Ettela’at, Kayhan was considered a “leftist” newspaper where censorship was a familiar phenomenon. Everyone knew about the restrictions in writing, so it was natural that Sahabi’s flight range in the sky of journalism could not be too expansive, especially since he was the type who avoided tension and sought compromise. It was obvious that Sahabi had all the qualities needed to make a reputation for himself in the press industry. Being fluent in three European languages, the experience of living curiously in European intellectual society for five years, his fluent prose, speed in writing, competency in drawing and painting, and the camera that he always carried, made him a unique individual. But unfortunately these skills were not enough for him to grow under such circumstances. Sahabi was too independent and honest to deal with the graft that was common within press circles. As he translated foreign reports and news, little by little he was drawn to Kayhan’s Art and Ideas pages, which were quite popular. He wrote many film reviews for the works of Kiarostami, Shahid-Sales, Mehrjui, George Lucas, Taviani, and Woody Allen, published under the alias of Sohrab Dehkhoda. He also wrote interesting reports about travels to the lands of Eskimos, Syria, India, etc. But none of these were what he expected of himself. His expectations for his career can be understood from an interview published years later in “Negah-e-No” magazine,

“…I have a habit that might be from my idealism, or some kind of hidden ambition, or my audacity, and that is whenever I start doing something I do it with precision and a professional expectation. I want my output to be at least professional…”

But the limitations faced by journalists at the time were great obstacles to his work.

On the eve of the revolution

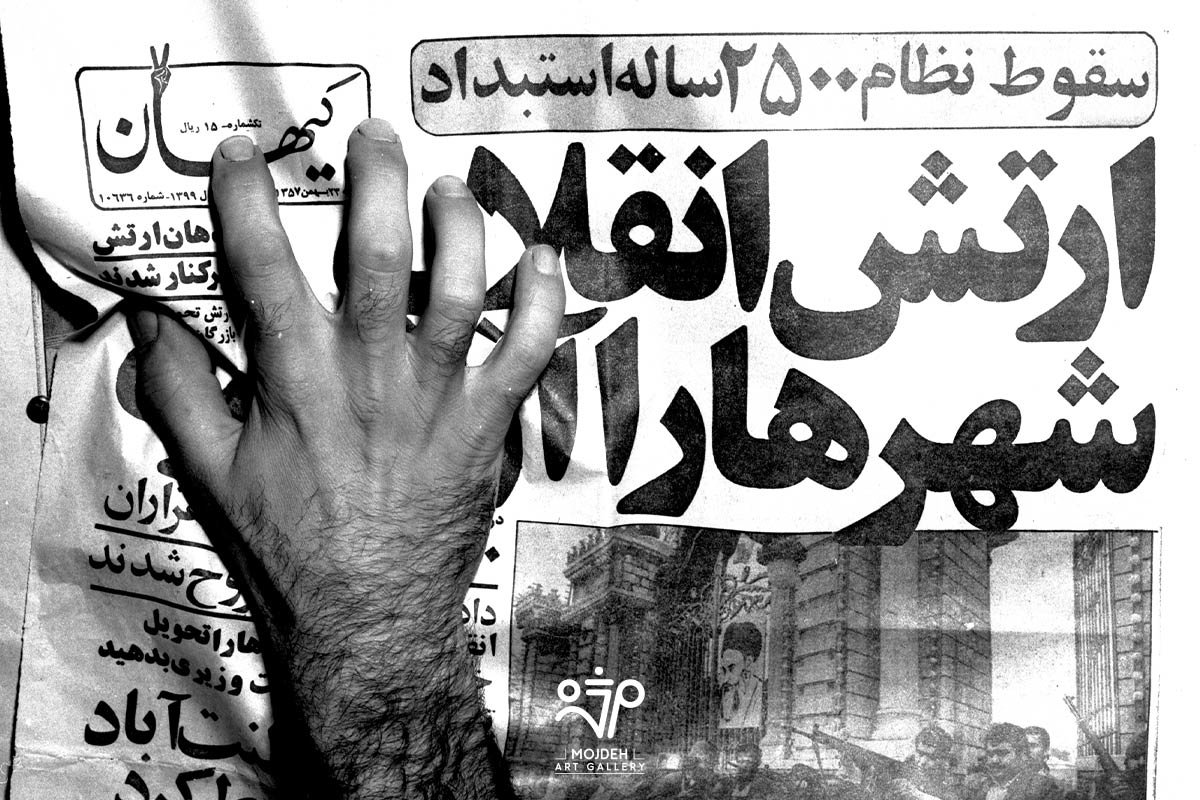

International developments and pressure from human rights organizations started a breeze that led to a bit more political freedom, but in 1978 this breeze was turning into a tornado that intended to blow away the old order. Recurring sociopolitical crises and uncontrollable socioeconomic protests and their reflections in the press, stirred up political discussions in press editorials. It was during these discussions that the mostly young journalists from different sections of Kayhan got to know each other better and created new groups. Martial law and the two-month long strike of the press, lead these journalists to call for the dismantling of the old order and demand more participation in running the newspaper editorial office. Their primary goal was to create an editorial board for Kayhan.

Mehdi Sahabi was a trusted and acceptable face among these young journalists and was known for his honesty, independence from the wealthy and powerful, and for being educated, independent in his thoughts and ideas, serious, and at the same time modest. There was much direct and indirect opposition against the demand for an editorial board. But this cause was aligned with the times and forced others to play along; after all there had been a revolution and the old order had already been dismantled. Finally on February 25, 1979, through an open election, the idealist journalists who weren’t yet corrupted by “the wheeling and dealing” of old organizational relationships, succeeded in adding two of their candidates, Mehdi Sahabi and Mojtaba Raji to the editorial board of five.

Despite his calm and pacifist character, Mehdi Sahabi accepted to play his historical role during that chaotic time, in a newspaper that had a circulation of over one million. But the creation of the editorial board not only did nothing to reduce tensions but also made things more complicated. External and internal pressures, made more difficult by behind the scenes deals, disrupted the management of the newspaper. Work became exhausting in these circumstances. But despite sabotages by the allies of Kayhan’s managers, who were trying to make them disreputable among the other employees, Mehdi Sahabi and Mojtaba Raji tried to perform their responsibilities flawlessly. Eventually some of the saboteurs came forward and told them blankly that this situation would continue unless they stepped down, which the two men declined to do. As days went by, the pressure increased. Ultimately on May 15, 1979, security guards prevented Mehdi Sahabi, Mojtaba Raji, and eighteen other journalists from entering Kayhan’s office. They were each given a letter that stated, “Based on the decision of the personnel, Kayhan newspaper is no longer able to work with you.”

It was not known who had signed the letter. The other editorial members stopped working and demanded their coworkers return. Finally, after enduring for one month, Kayhan’s editorial collapsed. Many left and a few remained. The behavior towards the dismissed journalists was very rude and disrespectful, to the extent that they decided to publish another newspaper under the name of “Kayhan Azad” (Free Kayhan). Most of the dismissed journalists, along with some others, took part in publishing Kayhan Azad newspaper on August 9, 1979. Mehdi Sahabi, Mojtaba Raji, and Javad Talei formed the editorial board of this newspaper. They stated that from the second issue, in honor of their coworkers at Kayhan, they would stop using that name “...which indicates years of work and the effort of hundreds of workers, employees and writers.” So from the second issue onward this newspaper was published under the name of “Azad”. Azad newspaper was confiscated as its nineth issue was being printed. Considering the context at the time the newspaper reflected only some of what was happening in society. Their intention was to avoid “extremism” and publish an independent and professional newspaper, but it seemed there was still a long way to go before they could reach this ideal situation.

Sahabi’s enthusiasm for publishing a professional newspaper, and his loyal friends who had stuck by him, prevented him from quitting journalism. He loved his job and with his undeniable abilities and having friends with the same mindset as him, he tried to publish a professional and independent newspaper. Even though many lost hope and left this work, he remained the axis connecting almost twenty journalists. They registered a company, rented an office on Enghelab Street, and worked in printing and cultural services until they could get permission to publish. In those days Sahabi showed how capable he was in managing a team flawlessly and setting an example. Even though he was the busiest of them all, he still translated, designed, and participated in the most trivial tasks. It was during this time that he published the book “The Conquest of Kayhan” under the pen name Younes Javanroodi.

Finally the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance accepted Mehdi Sahabi’s request for the right to publish a monthly magazine named “Piroozi” (Victory). The first issue of this sociopolitical magazine was published under the supervision of the Writers’ Council in October 1980. It was a publication that Mehdi Sahabi undeniably had the most important role in its creation. The goal was to present an impartial report of monthly events in Iran and around the world. All the published content in each issue was discussed and evaluated so that in the next issue the content would be better. Sahabi wrote editorials, translated, sketched, and even participated in the magazine layout. His role in publishing this monthly magazine was unparalleled. Everyone knew there would be no money from publishing this magazine, but they all worked tirelessly without any expectations, only to play a positive role in the most critical stage of the country’s press history. With all the effort to avoid any extremism, the acceleration of events and the incoming storm did not allow Piroozi to be published after its sixth issue in March 1980.

In search of another language

“…my initial experience was painting …, and as you know I also translate. But the field I have always continued in my life, despite all of its alterations, is painting. In other words I’m a painter by nature, but I have done other things as well.”

After Piroozi, Sahabi was looking for another language to express his feelings and emotions. He was like a bird that has many branches to make a nest on. Although leaving the world of journalism that he loved dearly was difficult, the experience taught him that his sensitive and peace seeking character could not tolerate its tensions and aggressions, so it would only be a waste of his time. He had lost the enthusiasm he had for journalism from 1978 to 1981. He was still an iconic presence in “Sanaat-e Haml-o-Naghl” (Transportation industry), “Film”, and “Payam-e Emrooz” (Today’s Message) magazines, but his heart was in working in another language. As he got further away from the world of journalism, colors and the canvas drew him in more and more. He took shelter in the world of painting, a world where he knew the language, and said, “… a scrapped car, a single portrait, and a piece of wood, all three are faces of the unique relation between the mindset of a person and reality. Any shape and even any improvement is a sign of communication, either between a person and himself “the artist and his mind”, or between a person and others “the artist and his audience”. In the end, all the elements of an artwork, no matter what they look like, “a scrapped car or a wooden flower” are the alphabet of a two sided conversation; one is the conversation between the creator and himself, and the other is his conversation with his audience… Isn’t it true that every language has numerous letters and thousands of words? And again, isn’t it true that even a unique word can have more than one meaning, and even these meanings are always changing? ” Mehdi had found a language and if his short life had allowed, he would have even been able to give flight to his birds!

Naser Tejareh