Caricatures with an Iranian Bite and Flavor

During the first months of the Islamic revolution, twenty-something caricaturists (otherwise known as cartoonists) were active in Iranian media. Unlike today, every day, week, and month, various works would be printed by them in different media, keeping their viewers informed, happy, and free from nameless fears. The spring of 1978 was a good opportunity to hold an exhibition of works by my peers, titled, “The first exhibition of visual humor artists”. I used the term “visual humor” instead of “caricature” in order to cover the great range of works and themes, but this was the first and last time when cartoonists from those years – with differing tastes and opinions – gathered together under one roof. Over the next few months, I collected original works from all except one or two of them. It became a unique, fiery collection covering the start of the revolution. A few of Tehran’s important galleries, refused to exhibit these for various reasons. But ultimately, without eliminating a single piece, an exhibition was held from October 16th to November 9th, 1978 at two of the main galleries of the Iran-America Association. The significance of this exhibition was not just in its revolutionary themes and historical collection; it was the independence of thought and unique creativity of every one of the artists whose work no longer required a signature, because it was the work of its creator.

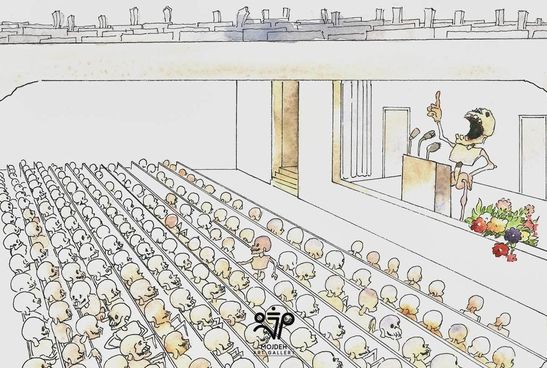

I referred to the past in order to come to the present time, when there are more than a thousand cartoonists active in Iran, with good penmanship and excellent technique. But each time I attend the biennial caricature exhibition in Tehran, except for around twenty artists, I am unable to differentiate the work of my countrymen from those of international caricaturists – particularly eastern Europeans – if it weren’t for the labels next to the works. The exhibition is lacking a hundred “Bahman Rezaeis”.

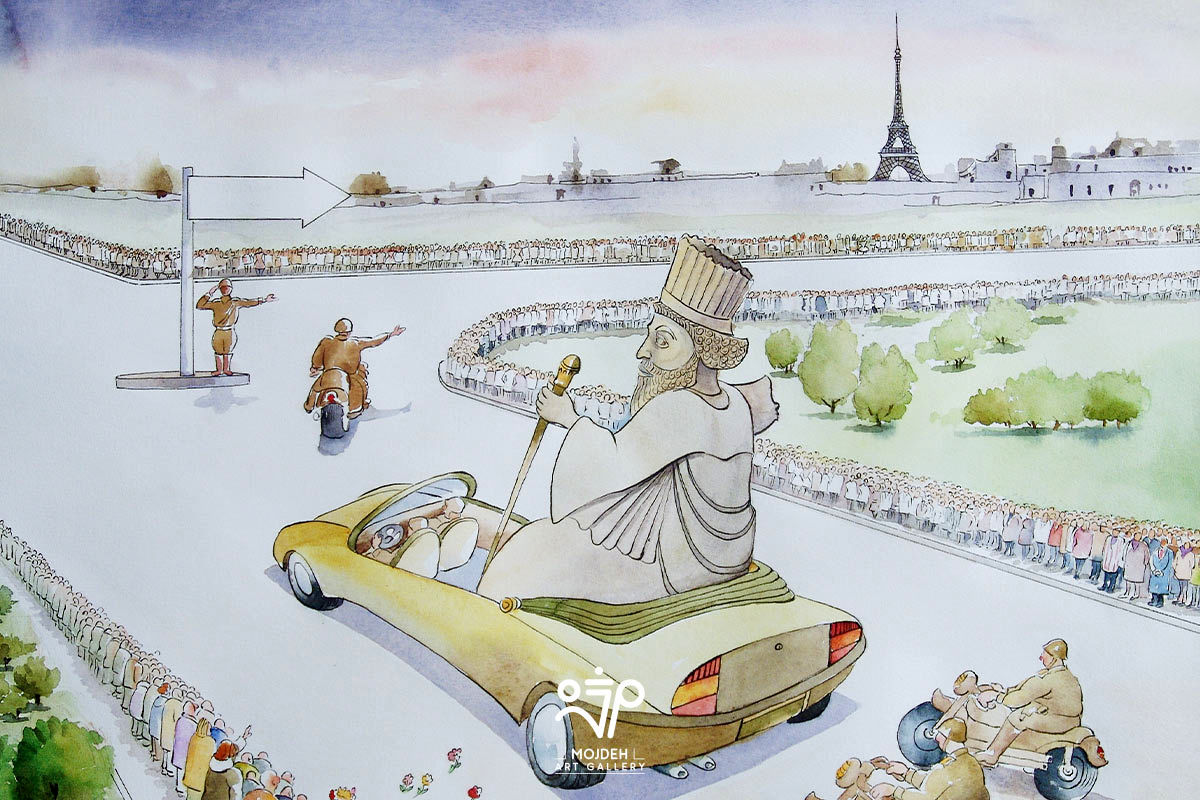

Bahman Rezaei is not just a pioneer Iranian cartoonist. With his unique style that has no equal in the world – even among Eastern Europeans! – he is one of the established figures in the field. The most characteristic feature of his work, which even sets him apart from some of his peers, is its Iranian bite and flavor. Caricatures and cartoons are universal arts, but geographical determinism shapes its expression, tone, accent, and native and national identity. There are undoubtedly other Iranian cartoonists who have tried and succeeded in creating works with such characteristics. In the mid-1960s Ardeshir Mohasses’s attempts at creating caricatures based on Iranian miniatures was an auspicious move, which Kambiz Derambaksh later elevated with his black miniatures. Bahman Rezaei’s work, especially his most recent pieces, is also inspired by Iranian painting and based on the peculiar relations of Iranian society. He displays a kind of Iranian point of view, for example in the encounter of tradition with modernity, which produces a bitter laughter and a form of sarcasm.

This form of humor and sarcasm is not specific to Rezaei’s new works and experiences. A glance at his work from the 1960s to the 1980s shows that like many of his generation, and unlike Iranian caricaturists from the late 70s onwards, whose work addressed intellectuals and elites, Rezaei should be considered a “street” caricaturists, not in its common definition, but as someone who communicates with a wide range of people from all segments of society without creating unnecessary twists in his work. It goes without saying that these types of caricatures, that go against worn habits and miserable routines, and address the general public in plain form, are more effective than works that aim at the tip of the social pyramid with a philosophical, noble (and sometimes snobbish) attitude.

Most of Bahman Rezaei’s subjects over three decades have covered the problems and troubles of the petty middle class in the guise of double-faced craftsmen, shameless employees, professional policemen, and stylish, talkative women (and of course naughty children!). If a book of these works were to be printed, it could be placed alongside Jafar Shahri’s books on social history.

Since the early 1990s, Rezaei has created works with the same clarity of tone and vision as before, but set on a new context where he embarks on new experiences. The use of "Miniacature" as an illustrated history of Iranian national identity, as well as the use of signs and symbols from the Achaemenid era, and combining them with social symbols of the contemporary period in order to show individualistic anarchism and pervasive narcissism (and anything else you receive from these designs) is quite funny and shocking.

In his collection of "Miniacature", a Mercedes Benz has stopped in the middle of a historical landscape. Its arriviste and hedonistic driver invites the women woven into a carpet hanging on the wall to join him in a secluded area, to do as you can imagine. It is as if Rezaei has illustrated a new chapter in history.

Bahman Rezaei’s style is indeed reminiscent of the simple and playful world of the inner-child.

Massoud Mehrabi