Even the Dead Can Be Happy

Dear Bahman Rezaei,

In your recent caricatures you attended to a subject that is close to love and life in our world, but seems even more comprehensive than that: “the world of the dead”.

Death is man’s oldest concern, and also the most recent when the sound of mourning rises from a neighbor’s house. We live inside the body of death and walk shoulder-to-shoulder with the dead. Every morning, with their presentation of local and global events, the media remind us of the inevitable fact that we are as close to death as we are to life. Just like history, politics, and widespread catastrophes; literature, art, and mythology form our attitudes towards mortality. But awareness of death is not the same as an obsession with it.

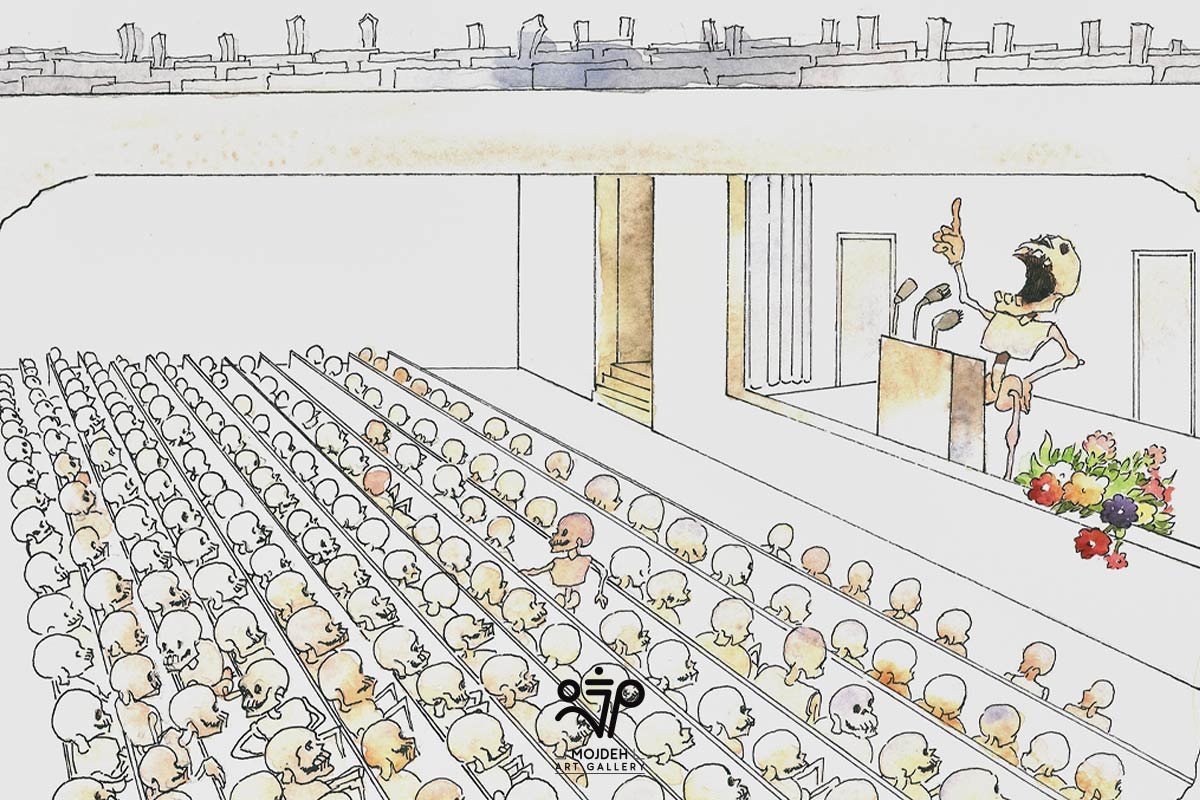

The cult of the dead is only the preoccupation of passive death worshippers, but you humorously worry and laugh at this taboo. Death is terrible everywhere and in any situation, because it is a failed ending. It makes one sad and fearful. But you, dear friend, are not afraid of death and mock it in your work. Or perhaps you scoff at it out of fear. Whatever it is, I see the artist smiling sarcastically at the world of the dead, and this is an innovative approach to an ancient topic. The idea of death has imprisoned thought in human life, and the fear of annihilation has filled the world of the living with terror. It is such thoughts that have left people helpless at the edge of fear and vain hopes, allowing the wise and powerful to paralyze the masses and fill their minds with anything that can make the foundations of their authority permanent. For a long time now, modern thinkers have been wondering about the concept of death, and you have spread out ideas about death at the right time, forcing the merry dead-thinkers into the underground festivities of life.

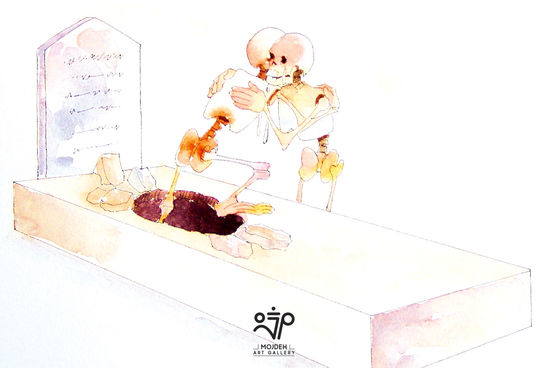

With a clever trick, you have changed the place of the living and the dead in your work, and have allowed the dead the freedom to live again in a humorous virtual space. You have tore down a boundary, a line that forms an artificial border between the living and the dead. In your work the living (those who weep over graves and mourn at funerals) are connected to the dead, and it is clear that you have become bored with this crowd of weepers and hence have depicted them as a group of faceless, identical figures. But it is your dead that actually have a real life. In the underground world of the silenced, hidden from others, they celebrate and make noise and enjoy themselves. They watch satellite TV, bask in the sun next to the pool, entertain themselves in high, underground towers, and watch concerts without fear of anything (or anyone) disturbing their fleeting pleasures.

Your caricatures that have joyful colors, celebrate death with cheerfulness, turning the rites of the dead into pleasures of everyday life. It seems like in their underground world, the dead are doing everything they couldn’t do in life. But where is this underground world? Why does life become underground?

It is not the artist’s task to answer this question, but with lightness and sense of humor you have shown us how it is done. There is no room for grief in this world of nonexistence that is filled with joy. Grief remains above ground, in the ceremony of the tearful and weeping survivors, who should mourn for themselves rather than those who are gone. The departed are underground and have no need for tears, even though every once in a while, the flood of tears from above provides water for their fishpond. Yet, the living dead have their own dreams, fears, and hopes. From the fear of changing graves, to unrelated neighbors, cheerful weddings, concerts, private romantic affairs, as well as solitary and group excursions. Sometimes the humor is multi-layered:

The bride and groom, who do not require any covering for their wedding night, are dressed while the guests are nude skeletons.

Or the bearers of a heavy corpse wish it to be crushed by a boulder one more time.

Or the wishes of the dead for being massaged by angels should make their torments heavier, but there is no punishment involved. What greater punishment than a past life? “What more is there to fear now, given the state we are in?”

In some of your works life takes place not in the underground world of the dead, but in the border between the two worlds. In one of your pieces a grave is enclosed between long bars. On the left side, two trees are so lovingly intertwined that they make life on earth spectacular and humane. We see how existence boldly withstands non-existence in the form of a plant ascending from the underground of pleasure, to reach the space above ground, which is filled with regret. Or the tip of a skyscraper breaking through the fake border between life and death, revealing the majesty of those who are underground.

With these works you have taken a bold step in your middle age, and I welcome you to the club of serious satirists. I am glad that you were able to show us a humorous version of death. You have laughed at the great tyrant called death, and have invited us to laugh along with you. And you have done this with delicate penmanship, and with strong compositions, inspired by traditional painting (especially miniatures). The design of a wild but joyous atmosphere requires youthful boldness, and you have made the dead, and those living with dead hearts, happy.

Post Script

You entered the realm of caricature art on a global scale as an artist and designer in 1994 in an exhibition on Miniacature and carpets at Golestan Gallery.

Richly patterned carpets as exquisite hand-woven Iranian artifacts, which reflect the imagination of our folk art, became a cinematic background where familiar heroes and celebrities came to life in order to present new relationships of love and hatred, war and escape, and to create a surreal atmosphere that was not far from our surrounding reality and context.

In your next exhibition at Vali Gallery (2008), the kings and soldiers depicted in stone engravings (at Persepolis) were able to appear in the present time, and show their vulnerable presence as a catastrophic absence. You showed to what extent mythological symbols and historical signs could come close to the present time, and if they could be safe from abuses and unreasonable reactions and play a harmless role in our day-to-day lives.

By bringing the past into the present, whether in the form of motifs and events woven on carpets or carved in stone slabs, you invite us to a joyous atmosphere, where unexpected relationships and inverse situations between human beings and animals becomes a source of laughter. Your designs have gradually become tighter and your compositions stronger. And your most recent works on the theme of the carpet, which has not yet been exhibited, is more suitable for being exhibited in a contemporary art museum rather than being printed in a newspaper.

Javad Mojabi

September 23, 2006 / Writer’s Alley